Europe

Giving a paper entitled ‘Europe: the view from elsewhere’ at a conference on Theorizing Medieval European Literatures just days after the UK voted by a narrow margin to leave the EU was poignant. This marvellous conference (see the programme), organised by the Centre for Medieval Literature of York and the University of Southern Denmark, brought together specialists on a broad range of European and non-European languages to discuss whether ‘Europe’ is a meaningful category for the study of medieval literature. Had my title proved prophetic? Could it be that shortly the UK would provide a view from elsewhere?

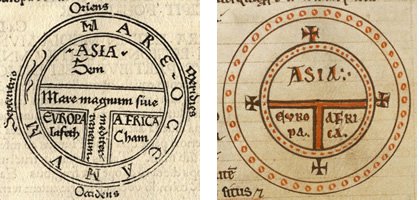

My argument was simple. Whereas there is broad consensus among historians that the idea of Europe was rarely productive before the fifteenth century, that the word ‘Europe’ was rarely used in medieval texts, and that when it was used it was exclusive or normative, I showed that vernacular writers frequently appealed—implicitly and explicitly—to the tripartite division of the known world into three continents: Asia, Europe and Africa. This model is best encapsulated in the widely reproduced so-called T/O map, which represents the world’s known landmasses as a circle surrounded by the sea and divided into three uneven parts, with Asia occupying twice as much space as Europe and Africa, and with the Mediterranean as the central divider. The three parts of the world are associated with Noah’s three sons, who each have a part of the world conferred on them after the flood:

T/O maps of the world from manuscripts of Isidore of Seville

One reason why these maps are so interesting from a modern perspective is that they do not offer a Eurocentric representation of Europe and the world. Indeed, Asia dominates this world view both through its size and its position. As is well-known European maps do not routinely use a north-south axis until the fifteenth century, and it is not until this happens that the Eurocentric world map with which we are familiar becomes possible. Yet world maps like this are frequent in the European Middle Ages (particularly in manuscripts of Isidore of Seville) and they always set Europe in relation to the other two continents, not at the centre of the world.

The use of elephants symbolises the military might of Asia, from BnF, f.fr. 20125, f. 260r. Source: Gallica.BnF.fr.

The idea of Europe encapsulated in the T/O map does not implicitly or otherwise claim superiority for what scholars of medieval Europe generally regard as its centre (Northwestern Europe). On the contrary, Europe is represented as dominated by Asia, and Northwestern Europe as peripheral to the centre of the world. Of course some maps place Jerusalem at the centre, but this is a superimposition on an earlier model, which has the Eastern Mediterranean—the Greek world—as the focus, a Greek world explicitly positioned in between the three known continents. If we take this ubiquitous model seriously then it is not true that Europe has little weight as a category in the Middle Ages; it would be truer to say that it did not mean the same things as it came to mean from the late fifteenth century onwards, and that this has led modern scholarship to fail to recognise the extent to which Europe was indeed a productive category in the Middle Ages. Francesco Stella’s paper on ‘Europe and European in medieval Latin texts’ offered a counterpart to my paper at the conference last week in showing that ‘Europe’ continued to be evoked frequently in Latin texts, whatever the historians tell us.

So far we have transcribed approximately one third of the Histoire ancienne in BnF f.fr. 20125 and we have found 15 occurrences of the word Europe. It is a common point of geographical reference in the text, which explicitly makes reference to the tripartite division of the world, which the compiler-author would have found in one of his main sources—Orosius—as well in a host of other standard texts:

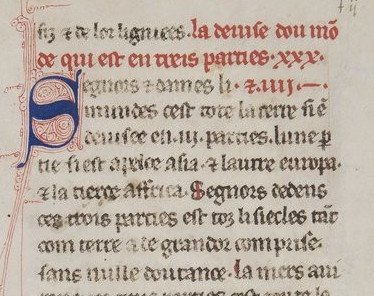

BnF, f.fr. 20125, f. 11r. Source: Gallica.BnF.fr.

Segnors et dames li mundes c’est tote la terre si e[n] devisee en ·iii parties· l’une p[ar]tie si est apelee Asia· 7 l’autre Europa· 7 la tierce Affrica· (f. 11r)

My lords and ladies the world, that is the whole earth, is divided into three parts, one part is called Asia, and the second Europe and the third Africa.

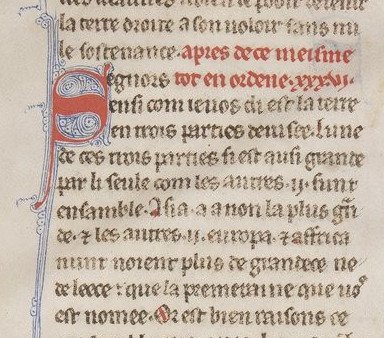

BnF, f.fr. 20125, f. 11r. Source: Gallica.BnF.fr.

Segnors ensi com ie vos di est la terre en trois parties deuise· l’une de ces trois parties si est ausi grande par li seule com les autres ·ii· sunt ensamble· Asia· a a non la plus g[ra]nde· et les autres ·ii· Europa et Affrica n’unt noient plus de grandece ne de leece que la premeraine que vos est nomee· (11v)

My lords, as I have told you the earth is divided into three parts. One of these three parts is by itself as big as the other two together: the biggest is called Asia, and the other two, Europe and Africa, are scarcely larger nor more prosperous than the first one I described for you.

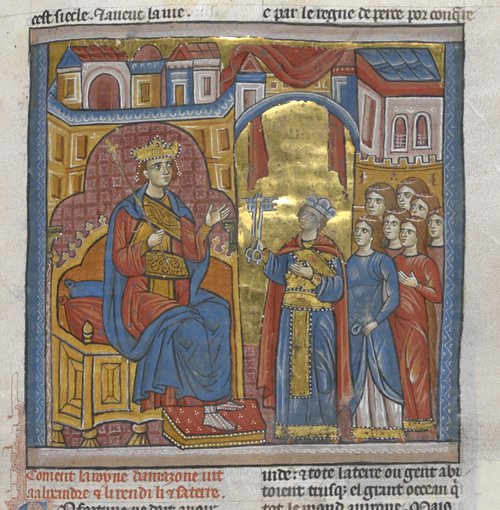

The Histoire ancienne narrates the marvels and might of Asia in various sections, but in particular in the story of Alexander the Great. From London British Library, Add. 15268, f. 203r. Reproduced with the permission of the British Library Board.

The Histoire ancienne narrates the Trojan origins of a host of places many of which are explicitly flagged as en Europe: Sicily, Rome, Venice, Britain, Germany. Europe, in this mythology, demonstrates unity and connectedness, historically and geographically. Europeans share more than divides them in this account; they are ultimately connected to the rest of the world thanks to their cultures’ Asian origins. The origin of European peoples and cultures in the movement of Asian migrants is widely recognized in medieval vernacular literature. Meanwhile medieval accounts of travel to Asia—in both Latin and the vernacular—frequently acknowledge the cultural and technological superiority of Asia, also often portraying societies in which Christians, Muslims, Jews and people of other religions live side by side. All this is at odds with the usual account of the medieval world as intolerant, defensive and xenophobic. I am not seeking to deny religious intolerance in the European Middle Ages nor to make the Middle Ages into a panacea of diversity. Far from it. And of course the Mongol invasions, the expanding Muslim world, as well as the black death meant that Europe felt increasingly beleaguered. But the world view I am invoking does not suggest that ‘Europe’ was an exclusive or normative category.

The Values of French is a European project not just because it is funded by the EU, but because it is profoundly and proudly committed to taking a view of language and culture that is not bound by the straightjacket of the nation state. The TVOF team is unanimous and proud in declaring: nous sommes européens. Would that those of us with UK passports could remain so!

The TVOF blog is taking a break for the summer now. We will be back in September.

Read also David Wallace’s blog (After Europe, after Brexit) for his address at the Theorizing Medieval European Literatures conference. We fully concur with David's wise words about the potentially calamitous effects of the Brexit vote in higher education, in our field, and in the world generally.

Further reading:

Bartlett, Robert, The Making of Europe (London: Allen Lane/ Penguin, 1993)

Burke, Peter, ‘Did Europe exist before 1700?’, History of European Ideas, 1 (1980), 21-29

Curtius, Ernst Robert, European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages (London: Routledge Kean and Paul, 1953)

Mitterauer, Michael, Why Europe? The Medieval Origins of its Special Path (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2010)

Pagden, Anthony,The Idea of Europe: From Antiquity to the European Union (Cambridge: CUP, 2002)

Wallace, David, Europe: a Literary History 1348-1418 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2016)